The traditional garments of Cuentepec native women: notes on the kueuitl

ABSTRACT

A Mexican indigenous community called Cuentepec preserves the traditional women’s clothing known as kueuitl. The aim of this study was to explore the relationship between Nahua women from Cuentepec and their autochthonous dress. This ethnographic study primarily relied on participant observation, supplemented by interviews and bibliographic reviews. The photographs, reflections, and testimonies presented are the result of the researcher’s immersion in the community from May 2022 to January 2023. The research identified key elements of the traditional attire, concluding that it plays a fundamental role in the social dynamics of Cuentepec’s women.

Palavras-chave: Indigenous garments; Indigenous culture; Traditional garments; Autochthonous dress; Cuentepec; Mexican garments; Nahua garments.

A vestimenta tradicional da mulher cuentepequense: notas em torno do kueuitl

RESUMO

Uma comunidade indígena mexicana chamada Cuentepec preserva a vestimenta tradicional das mulheres, conhecida como kueuitl. O objetivo deste estudo foi explorar a relação entre as mulheres nahuas de Cuentepec e sua vestimenta autóctone. Este estudo etnográfico baseou-se principalmente na observação participante, complementada por entrevistas e revisões bibliográficas. As fotografias, reflexões e depoimentos apresentados são o resultado da imersão da pesquisadora na comunidade entre maio de 2022 e janeiro de 2023. A pesquisa identificou elementos-chave da vestimenta tradicional, concluindo que ela desempenha um papel fundamental na dinâmica social das mulheres de Cuentepec.

Keywords: Indumentária Indígena; Cultura indígena; Vestimenta tradicional; Vestido autóctone; Cuentepec; Indumentária mexicana; Indumentária nahua

La vestimenta tradicional de la mujer cuentepequense: apuntes en torno al kueuitl

RESUMEN

Una comunidad indígena mexicana llamada Cuentepec conserva la vestimenta tradicional de las mujeres, conocida como kueuitl. El objetivo de este estudio fue explorar la relación entre las mujeres nahuas de Cuentepec y su vestimenta autóctona. Este estudio etnográfico se basó principalmente en la observación participante, complementada con entrevistas y revisiones bibliográficas. Las fotografías, reflexiones y testimonios presentados son el resultado de la inmersión del investigador en la comunidad entre mayo de 2022 y enero de 2023. La investigación identificó elementos clave de la vestimenta tradicional, concluyendo que esta desempeña un papel fundamental en la dinámica social de las mujeres de Cuentepec.

Palabras-clave: Indumentaria indígena; Cultura indígena; Vestido tradicional; Vestimenta nativa; Cuentepec; Indumentaria mexicana; Indumentaria nahua

1. INTRODUCTION

Born in Cuernavaca, the capital of the state of Morelos in Mexico, I grew up in a middle-class family, where my parents worked all day and a nanny looked after me, whose name was Laura. Laura is from the community of Cuentepec, which belongs to the municipality of Temixco. She was a young indigenous woman who, like the vast majority of women in her community, left home for Cuernavaca in search of work.

She was a cheerful and very affectionate young woman who, having just arrived in the capital, was still mixing Spanish with her mother tongue, Nahuatl. Laura was naive, dreamy, and very vain; she was about twenty years old.

When I think of her, I always see her physical image. Every day, she wore the kueuitl (traditional clothing of her community), which consisted of a pleated dress in bright, cheerful colors and relatively short length (just above the knee), always accompanied by a colorful apron also pleated with a checkered pattern. When she left the house, she covered her back with a rebozo (a large piece of cloth used to help with childbirth); according to her, single women like her should wear the rebozo open, while married women should cross it. Walking down the street, she used to pay special attention to this detail, as she didn’t want to send out the wrong message.

I was just a child; I must have been less than ten years old, but we had a special relationship. She considered me to be fashion-savvy, and we would always talk about clothes. For example, she would advise me on which shorts and T-shirt to wear, and she would ask my opinion on the color composition of her dresses and aprons.

Laura spent a large part of her salary on her personal image and often asked for (traditional) dresses to be made. This fast-paced consumption was not so common in the early 1990s.

In her leisure time, Laura would meet up with her friends (all from her homeland) and spend the afternoon in the city center. On one occasion, I had the fortune of accompanying her. I don’t remember in detail what happened that day, but one image has remained in my memory: I was in the zócalo (the city’s main square) with a group of five or six women from Cuentepec, all speaking another language, all wearing the same dresses, in different colors, but the same shapes and patterns, all with checkered aprons and all wearing open rebozo, telling the world that they were single.

The experience of that day has marked my memory and made me realise that it wasn’t just Laura who had a special affection for those dresses, but all Cuentepec native women had a special relationship with that traditional garment.

These wanderings therefore aroused my curiosity to understand more about the link between garments and indigenous women. However, in addition to the curiosity that has accompanied me since childhood and the personal significance that this research may have, I believe that the field of fashion, the area in which I work, can benefit greatly from assimilating the experiences and interests of different identities and cultures.

Getting closer to those whom the system has always ignored, reflecting on the cultural constructs with which we have been formed, and questioning our own ways of doing things can help us reshape our role, detach a little from consumer culture, and find a broader understanding of human beings.

1.1 Method

The object of this qualitative research was the kueuitl (traditional women’s clothing from the indigenous community of Cuentepec). It was mainly an ethnographic study based on participant observation and complemented by interviews.

The main objective of this study was to understand the relationship between the indigenous women of Cuentepec and their autochthonous dress. The research was guided by the following questions: what does traditional women’s dress consist of, and how does it interact with women and the social dynamics of the community?

Data collection took place from May 2022 to January 2023, with a total of 27 field visits to the community, each lasting between 5 and 11 hours. Participant observation was the main tool of this investigation. Moreover, visits to the community were recorded in a field diary.

Throughout the process, I was assisted by a young local woman who acted as an interpreter (Spanish/Nahuatl), making communication possible because some of the population (mainly the elderly) only speak the indigenous language.

The data presented here is part of a larger study and is the result of more than three years’ work.

To carry out this research, I had the support of the “Centro de Investigación en Ciencias Sociales y Estudios Regionales (CICSER) de la Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos (UAEM)” in Mexico.

I also had the support of the “Postgraduate Programme in Design at the Federal University of Pernambuco” in Brazil.

This study was conducted with the support of Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - Brazil (CAPES) - Funding Code 001’.

Observation: My involvement in the indigenous community of Cuentepec was not automatic; it had to be negotiated with Calixto, the municipal adjutant and political leader of the community, through a meeting where the objectives, procedures and intentions of the research were explained in detail. The negotiation was mediated by Father Fabio, the religious leader of the people of Cuentepec. After presenting my research project and obtaining the necessary permissions from the community leaders to carry out the fieldwork, Father Fabio and Calixto took advantage of a religious celebration to introduce me to the locals and warn the population of my presence in the community over the next few months.

2. THE CASE OF CUENTEPEC, MORELOS, MEXICO

2.1 The Nahuas

The state of Morelos is located in the central part of the Mexican Republic and is one of the smallest states in the country. It has a territorial extension of 4950 square kilometres, equivalent to 0.2% of the national surface, and includes 33 municipalities.

Morelo’s geography has certain geographical and climatological characteristics that encourage the existence and permanence of indigenous communities in the region (Hernandez, 2005, p.2). According to the National Indigenous Institute, indigenous peoples are spread across 16 municipalities in the state, and there are around 35 traditional communities living in Morelos.

The indigenous communities of the state of Morelos have been the object of study and work by different groups and individuals. Politicians, academics, artists, among others, have constructed their own images of indigenous communities and their people, who over time have been named and labelled with different titles: Indigenous, campesino, natives, minorities, ethnic groups, tlahuicas, among others. Today, the term that seems to be most accepted among government officials and academic communities to refer to the traditional communities of the state of Morelos is a generalisation that names all the indigenous people of the region as “Nahuas”. The term Nahua refers to communities that speak Nahua languages. Morayta (2011) describes that many of the state’s communities have assumed the title of “Nahuas” and other titles that “legitimize” them, in front of outsiders, as indigenous people to gain access to social development programs created by different governments. However, he highlights the fact that, among themselves (the indigenous communities), they have never stopped defining themselves as macehuales (the speakers of Mexican).

According to Hernandez (2005), the Nahua language family is approximately 45 centuries old. The word nahua means to speak clearly, with authority and with knowledge.

In the state of Morelos, most of these communities have access to dirt roads and streets that allow them to communicate with the most important urban and commercial centres in the region, such as Cuernavaca, Ciudad de México and Cuautla. Hernandez (2005) mentions that these conditions have favoured and boosted commercial and cultural relations between the indigenous communities and the city, resulting in acculturation processes among the indigenous people, mainly the loss of their language and traditional dress, but some of the communities have maintained their original culture in a more faithful way.

Cuentepec is one of the indigenous communities in the state of Morelos that is currently keeping its indigenous roots alive through its language, clothing, traditions and customs. In the Cuentepec native community, indigenous tradition is embedded in the daily lives of its people, in their most special moments.

Figure 1 - Dolls wearing the kueuitl. 2022, Cuentepec, Morelos.

Source: The author

2.2 Cuentepec

Etymologically, the word Cuentepec comes from kuémitl meaning “furrow” and tepetl meaning “hill”. Hence the name of the town means “furrow in the hill” in the nahua language. According to Landazuri (1997), this word describes the characteristics of the physical space in which the community is located.

According to INEGI (2020), Cuentepec has a population of 4001 inhabitants, 2026 women and 1975 men.

Cuentepec is an indigenous community that still maintains its traditional institutions of government and its system of civic-religious offices. According to Paz (2009), one of the main characteristics of Cuentepec that differentiates it from other communities in the region is how proud the population is of its Nahua tradition. Over the centuries, it has kept its language, clothing, habits, and customs alive (but not intact). According to the author, the conservation of tradition in the community has happened consciously and decisively. The vast majority of the population, both adults and children, speak Nahuatl. Elementary education in the community is 100% bilingual (Nahuatl and Spanish), and most of the women in the community, especially the elder ones, still wear the traditional dress also called kueuitl (figure 2). Paz (2009) recognises in Cuentepec an indigenous community that, through its daily practices and doings, reaffirms its tradition and deepest beliefs, its ethnic identity and its sense of belonging to the territory.

Figure 2 - Woman wearing the kueuitl. 2022. Cuentepec, Morelos.

Source: The author

According to Orihuela (2021), endogamy is a common practice in Cuentepec, as men and women often form their own families, marrying only members of the same community. According to the author, conserving this patriarchal practice has enabled the Cuentepec people to maintain their traditional way of life. Today, for example, it is still not accepted for people from outside the community to live in the region because there is a concern about not allowing people who do not share the same ethical principles and vision as the community to have rights over the territory.

2.3 Women’s clothing

Cuentepec is a community with strong and dynamic commercial and cultural relations with the big cities in the region. Most women work outside the community, mainly in the state capital, Cuernavaca, where they primarily undertake household chores. In addition, it is also expected to find them as kitchen helpers and producing tortillas by hand, as well as others working as seamstresses and shopkeepers.

These commercial/labour relationships mean that Cuentepec native women spend more time in the region’s big cities than in the community itself:

There is nobody here during the day (referring to the community); everyone queues in the morning, takes the bus to Cuernavaca, and only gets back at 8 pm. Most locals work in the capital during the day and only stay here in the evenings or at weekends (Father Fabio, 2022).

However, even though they spend much time away from home and socialising with people from the city, many of the women from Cuentepec do not allow themselves to be contaminated by other aesthetic references and still retain their original dress. Most adult women and some children and teenagers wear the kueuitl, the typical clothing of the community, every day.

This clothing tradition has been perpetuated over many generations since mothers, grandmothers, and ancestors used to dress in this way. The Cuentepec indigenous women’s attire is a unique and unmistakable symbol of their community.

2.3.1 The dress (kueuitl)

The Cuentepec woman’s garment consists of three main pieces: a colourful satin dress with a pleated bottom, a colourful apron, usually with a picture print and a pleated bottom, and a rebozo to cover her back (figure 3). Tradition states that unmarried women should wear the rebozo open, while married women should cross it.

Figure 3 - Cuentepec native dresses and rebozos. 2022. Cuentepec, Morelos.

Source: The author

All the garments (dress and apron) are designed and made by women in the community, except for the rebozo.

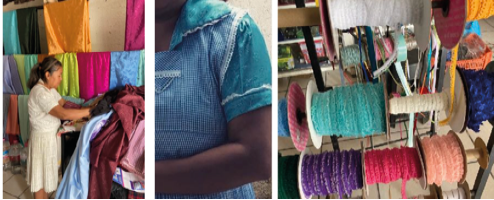

Two shops in the community (figure 4) sell the fabrics and trims needed to make the traditional garments. The main fabric used for the dress is a satin jacquard that in the community is known as “mismilia” or “mismilinque” because of its shine. The type of jacquard used is brocade. It is a thick, heavy fabric made using a jacquard loom and satin fabric, often with a rich floral pattern. The position of the threads makes this fabric very resistant, and, as a result, the community’s dresses generally have a long life. A checkered fabric called “tecido mascotin” is used for the apron. It consists of polyester and cotton and is ideal for this type of garment. The rebozo is the only garment not made in the community; it comes from the state of Mexico, where it is woven in a completely handmade process. The rebozo is a delicate and exclusive garment, and in the words of the women of the community, a very expensive one. The price of rebozos available in the community’s shops when I was conducting this research was approximately 1,200 Mexican pesos, equivalent, in the year 2023, to seven minimum daily wages in the state of Morelos.

Another essential aspect in the final composition of the dress, which can also be bought in local shops, is the trims (figure 4). The traditional dress can have some details and ruffles, mainly on the edges of the apron, pockets, sleeves and collar.

Figure 4 - Fabric and trims shop. 2022. Cuentepec, Morelos.

Source: the author

It is also possible to buy different colours of thread and yarn in local shops because when a woman has a dress made by a seamstress, she has to give her everything she needs to make it, including the thread, yarn and fabric. In the community’s shops, even though they are small, one can find absolutely all the materials needed to make the traditional dress.

2.3.2 The making

During my stay in the community, I had the opportunity to visit the workspace of Vicenta, one of the best-known seamstresses in Cuentepec (figure 5). She has been making traditional dresses for over twenty-five years. Her mother also worked as a kueuitl seamstress, and it was she who passed on all the knowledge Vicenta holds today. She regrets having had only male children and not having anyone to teach the sewing techniques she has mastered.

In Cuentepec, as in the rest of Mexico and most of the Western world, all matters related to clothing—creation, production, commercialization, etc.—are generally associated with the female gender and passed down from generation to generation through oral tradition.

Figure 5 - Vicenta and her workspace. 2022. Cuentepec, Morelos.

Source: the author

Vicenta makes approximately two dresses and an apron a day. It takes her approximately three hours to make one apron, two hours for sewing and one hour for ironing and pleating. It takes a little longer to make a dress. She says it used to take her a long time, but now she has gotten used to it and can do it more quickly. She only uses a Toyama domestic straight sewing machine inherited from her mother and can do all the finishing touches on the dress.

The price she charges for making the two pieces (mandil and dress) is approximately $140 (Mexican pesos). Equivalent to 80 per cent of a daily minimum wage in the state of Morelos in 2023. This amount also includes the ironing. She delivers the dress, pleated and ready to wear.

When clients come to her to order a dress, they must bring the fabrics and all the materials needed to make it. Interestingly, she does not take customers’ body measurements, but they have to bring along the fabrics, threads and trims, the cut and the size they want. In other words, they have to give the seamstress another dress that will serve as a basis for her to replicate.

Two metres of fabric are needed to make the dress and another metre and a half to make the apron. Vicenta says that the most challenging part of her job is making the skirt and the pleats. The first step is to cut the fabric. She does not use paper moulds. The only reference for cutting the fabric is the dress that the same client brought. Once she has cut out the skirt, she starts to “tabulate” it, a process in which she uses her fingers to make the pleats in the skirt manually and then sews them to the skirt’s waistband or the top of the dress. Once the finishing touches have been made on the sewing machine, she proceeds to the pleating process (figure 6), which consists of ironing the skirt to form the pleats.

Figure 6 - Pleating process. 2022. Cuentepec, Morelos.

Source: the author

The dress is then customised according to the customers’ wishes. Some like to add a ruffle on the chest, others prefer without.

2.3.3 Two generations, two dresses

Walking through the community streets, one can see two types of traditional dress (figure 7). The first and most common is the one already mentioned here and described in advance. The second is its predecessor. Approximately 50 years ago, the traditional Cuentepec dress consisted of a separate blouse and skirt, an apron (just covering the skirt) and a rebozo.

They used to make them as short skirts; now they’re complete dresses. Before, there was a skirt and a blouse, similar to this one, but it’s different. The elderly ladies, over 60, still wear them like this; the younger ones wear the dress. I don’t know why it’s changed, it’s been worn like this since I was a child. (Alejandra, 2022)

At some point in the 20th century (there is no consensus on when or why), the traditional female dress of the Cuentepec native community changed from a skirt and blouse to a dress with an apron that also covers the top of the dress. The senior women of the community still wear the old form, blouse and skirt, while the younger women only wear the dress.

Figure 7 - Cuentepec dress, two generations. 2022. Cuentepec, Morelos

Source: the author

Another clear difference between the two generations is the pleating of the skirt. While the pleats on the younger women’s dresses are tiny, the pleats on the elderly women’s skirts are considerably larger: “Some wear the dress with very small pleats and others with longer pleats. The elder ladies wear the larger pleats, the younger ones wear the very small pleats.” (Carla, 2022)

These variations result from the complexity of the pleating of the garment. The pleating work done by Cuentepec native women is very meticulous; some of them make a pleat smaller than a centimetre and it is clear that keeping this dress well ironed, with perfect pleats, is a complicated task that requires a lot of time and effort. The elderly woman from Cuentepec does not have the same strength and disposition to iron her clothes as young women, which is why the pleats in her skirt are larger.

The image above (figure 7) clearly shows these differences: on the right, a senior woman is wearing a two-piece garment (a blouse and a skirt). It is pleated with larger pleats. Meanwhile, on the left, a younger woman is wearing a one-piece garment with a pleated skirt with small, joined pleats.

This kind of change in traditional clothing makes sense when looked at through the cycle of tradition proposed by Herrejon (1994). According to the author, for tradition to really prevail over time, there has to be correspondence. In other words, tradition has to be cyclical:

a) The cycle begins with the action by virtue of which something is transmitted

b) This action is followed in correspondence by the reception of what has been passed on

c) Along with reception, a process of assimilation begins: the transmitted content becomes part of the recipient, and at the same time, the recipient adjusts and recreates the content. The assimilation of tradition implies the actualisation of that tradition.

d) Once assimilated, tradition enters a phase of stability, but stability does not mean immobility. In this phase, the recipient keeps what they have received as a heritage because otherwise, there would be no identity, but at the same time, they enrich, reduce or modify what they have received. This dynamic means that tradition retains its vital character.

e) In this last phase, along with possession, transmission returns once more, so the cycle ends.

Reflecting on Cuentepec traditional dress through the cycle of tradition helps us to understand its dynamism. For tradition to remain in time, it has to go hand in hand with it. According to Herrejon (1994), tradition is succession in time; it is a temporal process, and as a temporal process, it is change: all the change necessary to continue. Following this cycle, the Cuentepec dress of past generations has been received, assimilated and transformed into a one-piece dress.

This change process has allowed it to survive and reproduce without losing its fundamental identity, thus helping to give cohesion and unity to the group as a whole.

2.3.4 Clothing in the social dynamics of the community: the scapular ritual

The identity of Cuentepec native women is reinforced daily through their clothing. Cuentepec traditional dress plays an essential role in the social dynamics of the community. One of the indigenous Nahuas’ most popular traditions is the mixo or scapular ritual.

The scapular is a “ritual that derives from an illness of cultural affiliation in some of the indigenous communities of the state of Morelos” (Gonzalez, 2020). The ritual aims to cure the “mixo” or “scapular disease” and alleviate its symptoms. Symptoms can vary from person to person, but some of the most common manifestations of the disease are headaches, stomach pain, diarrhoea and vomiting. The treatment for this disease consists of giving the sick person a scapular with the image of Santo Domingo.

The scapular ritual gives rise to a conviction that religious conceptions are valid and religious directives are correct. Geertz (1989) talks about the importance of rituals for traditional societies because it is through the consecrated behaviour of rituals that “the lived world and the imagined world merge under the mediation of a single set of symbolic forms, becoming a single world and producing that idiosyncratic transformation in the sense of reality” (Geertz, 1989, p.82).

According to Gonzalez (2020), scapular disease has been part of the community for many years, and the ritual to treat it is one of the most important in the Cuentepec indigenous tradition. The ritual begins with the diagnosis of the disease. The person begins to show specific symptoms that usually lead them to visit the doctor. However, if the discomfort does not go away after the visit to the doctor, it is assumed that it is a mixo or scapular disease. Next, the patient needs to be taken to the community healer, who will confirm the diagnosis and reveal the name of a person (it can be anyone in the community) who will play the role of godfather or godmother and who will be in charge of delivering a scapular to cure the patient (hence the name of the ritual and the disease). According to Gonzalez (2020), this marks the commencement of a rupture from daily life, and the ritual begins to manifest within the realm of sacred time:

The first measures after detecting the disease must be immediate; for this reason, the godparents tie green and red ribbons around the patient’s ankles and wrists to stop the symptoms. They then wait eight days, during which time some people may be cured; if the patient has been healed, then the ritual ends. However, if this doesn’t happen, they start “giving the scapular”. From this point on, you enter a new rhythm (that of the community) and a new space (that of the festival). In a relatively short period of time, the family has to start preparing for the “scapular” feast, i.e. arranging the necessary materials, food and drink, arranging the band, the sound equipment, and everything necessary to cater for the godparents and guests at the ritual (Gonzalez, 2020).

The ritual party begins when the patient’s family brings food and drink to the godparents’ house. There, everyone (godparents and the sick person’s family) drinks until they are drunk, and then everyone walks to the sick person’s house to hand over the scapular.

Upon arriving at the patient’s location, the initial step is to lay a mat on the floor, which will serve as a place for the godparents to assist the patient in changing into a set of red attire. For women, this attire typically consists of the traditional dress of the community:

you have to change the sick person’s clothes in front of everyone, put on a red dress if you’re a woman, or trousers and a shirt if you’re a man. The clothes have to be all red, and it has to be the traditional dress (Carla, 2022)

Emphasising the pivotal role of the kueuitl in the ritual is essential, as the healing process commences with the specific act of changing clothes. It is important to mention that, according to tradition, the dress can only be red: “The dress has to be red because Santinho says that he only likes red; we call Santo Domingo Santinho. He only wants red dresses.” (Carla, 2022)

According to Gonzalez (2020), all the ritual elements, including clothing, play a fundamental role in the patient’s recovery because they provide an opening to a sacred dimension. In the ritual of the scapular, the dress becomes a code of entry into the festive time and space and will, along with other symbols of the celebration, be responsible for the patient’s healing.

The process of healing the sick person through the ritual aligns with Laraia’s (2007) assertion that culture wields profound healing influence. According to the author, the belief that the afflicted individual invests in the remedy’s effectiveness or the influence of cultural intermediaries can facilitate recovery from both actual and perceived ailments.

The ritual of the scapular makes evident the importance of clothing for the women of the community because, in the celebration, the traditional red dress becomes a liturgical object. This sacred symbol contributes to the dignity and beauty of the ritual. Without the red dress, there is no celebration or ritual; without the red dress, there is no cure for the disease.

2.3.5 What about sleeping?

An interesting revelation from this research was discovering that the traditional Cuentepec dress is also worn at bedtime. I learnt this detail by chance, spontaneously, while talking to a lady about how many dresses she had and how the fabric sold in the community was resistant and lasted for many years. Talking about her dresses, she mentioned that even when they were old, they did not discard them because they were also used for sleeping.

When she mentioned this detail, I was astonished. Until then, I had never considered including a question in the interview script about the clothes the women slept in because I had never imagined that the same dress would be used for resting. From then on, I incorporated this question into the interviews. The answer again surprised me: most women said they slept daily in their traditional dress and used older, worn-out dresses for this purpose.

According to them, when it is time to go to sleep, they take off the apron and lie down with just the dress, as sleeping with both garments would be very uncomfortable. In winter, when the weather gets freezing, some of them (the younger ones) wear sweatpants under their dresses, but this only happens when the temperature is very low because they do not feel comfortable. When this happens, they take off their trousers before they get out of bed because they do not want to be seen like that.

At first, the kueuitl did not seem like the best option as a sleeping garment. My first reaction was to think it would be an uncomfortable garment, but I did not have to investigate too much to discover that I was wrong.

Comfort plays a pivotal role in determining the quality of an individual’s sleep, with numerous factors contributing to it. Nevertheless, as per Song’s insights in 2011, discussing comfort can be intricate due to its subjective nature, susceptible to psychological and physiological influences from various environmental conditions.

It is worth noting that clothing, owing to its proximity to the body, is significant in attaining human comfort. Das and Alagirusamy (2010) attribute comfort in clothing to four basic elements: thermophysiological, sensory or tactile, psychological and ergonomic. So, I decided to look for the elements proposed by Das and Alagirusamy within the Cuentepec traditional dress.

The thermophysiological element corresponds to the garment’s heat and humidity transmission characteristics. Given that Morelos is renowned in Mexico for its agreeable climate, and the community of Cuentepec boasts an annual average temperature of 27°C, the short dress emerges as a practical choice for unwinding during the predominantly hot days that characterise most of the year. The problem is easily solved when the temperatures drop, as the women interviewed said, with a sweatshirt under the dress.

The sensory or tactile element pertains to the array of neural sensations experienced when a textile makes direct contact with the skin. Since Cuentepec native women regularly wear these fabrics, sensory comfort is not an issue. This is particularly true when wearing older dresses, which often feature frayed textile fibres, creating a more pleasing tactile sensation: “I wear (to sleep) my yellow dress because it’s the softest and it feels really nice. This dress has been with me for over twenty years” (Juana, 2022).

The third comfort element mentioned by the authors is the psychological one, which has little to do with the technical characteristics of the clothing. For many Western societies, psychological comfort often intertwines with the realm of fashion, where the perception of status associated with a particular garment can bring satisfaction to the wearer. Conversely, for the women of Cuentepec, even though their traditional dress may not align with the fashion phenomenon, it holds a unique psychological comfort. It imparts a sense of aesthetic comfort, which becomes apparent in Angelica’s words when she describes her bedtime routine on chilly nights:

In December, when the weather gets really cold, I sometimes wear my sweatpants to bed. I only have one pair of trousers, and I wear them under the blanket because I don’t like anyone at home looking, so I take them off in the morning before I get out of bed (Angelica, 2022).

In this account, it is easy to recognise the pisco-aesthetic comfort that the kueuitl provokes in the Cuentepec native woman, as she prefers to be observed only when she is wearing the traditional dress because it gives her a feeling of confidence and well-being.

The fourth and final element, which refers to the ergonomic aspects of clothing, is generally related to the garment’s shape. In the interviews, all the women emphasised the fact that the apron was not used for these purposes because, as it is a garment that is tighter to the body, it would be very uncomfortable when sleeping. According to Das and Alagirusamy (2010), the garment’s fit and structure is the primary factor that significantly impacts ergonomic comfort. In this regard, the Cuentepec dress holds a distinct advantage due to its pleating design, as the pleats in the skirt provide women with enhanced flexibility and freedom of movement.

When we examine the attributes of the Cuentepec dress from the perspective of Das and Alagirusamy’s theoretical framework (2010), it becomes evident that Kueuilt perfectly aligns with all the criteria essential for comfort. Not only does it serve as a practical garment for relaxation, but it also offers aesthetic comfort to the women of the community.

2.3.6 How many dresses does a woman from Cuentepec have?

According to Pineda (2024) one of the main characteristics of traditional women’s clothing in Cuentepec is the variety of colours. Walking through the community streets, one can admire the different shades of fabric and the different compositions formed by overlapping dresses and aprons. The vast diversity observed has aroused my curiosity to learn more about the number of dresses and the colours that make up the wardrobes of the women of Cuentepec.

This study involved surveying the community’s central square, where several local women adorned in traditional dress responded to a set of prompts based on a guiding question: How many dresses do you have at home, and what colours do you use the most?

The results were varied and are presented below (Table 1). The representative group was made up of a total of twenty-five women, and their answers were placed in one of the following ranges:

Table 1 - Dresses per capita

|

HOW MANY DRESSES DO YOU HAVE? |

|

|---|---|

|

INTERVAL |

FREQUENCY OF RESPONSE |

|

From 10 to 20 dresses |

0 |

|

From 20 to 30 dresses |

11 |

|

From 30 to 40 dresses |

5 |

|

From 40 to 50 dresses |

2 |

|

From 50 to 60 dresses |

2 |

|

From 70 to 80 dresses |

0 |

|

From 80 to 90 dresses |

0 |

|

More than 90 dresses |

3 |

|

I don’t know |

2 |

Source: The author

Here are some intriguing discoveries: to start with, not a single one of the women reported having fewer than twenty-five dresses, and some even mentioned having over a hundred.

When it comes to purchasing materials to have dresses custom-made by a seamstress, they all share a common preference for a diverse range of colours. In essence, they make it a point to select fabrics in shades they do not already possess in their collection at home. Interestingly, none of the twenty-five participants had a traditional black dress; none of them could answer why, but black is not part of their wardrobe, and black fabric is not even sold in the community’s shops.

When I asked them about the rebozo and how many pieces they had at home, almost all of them said they only had one or two; they said they did not have any more because the rebozo was very expensive.

When questioned about the reason for having such an extensive dress collection, their response indicated a preference for a broad spectrum of colours. Additionally, they explained that a significant portion of their dresses consisted of older pieces, as, in their experience, these dresses maintained their excellent condition over an extended period. Some women told me that they had dresses that were more than thirty years old. This information aligns with what the saleswoman at the fabric shop mentioned during my visit. She spoke highly of the quality and durability of the materials used in traditional clothing, reinforcing the observations made. According to the saleswoman, the jacquard, the fabric used to make the dress, is one of the most resistant on the market. Moreover, the mascotim, the fabric used for the apron, is even more resistant.

Hence, it can be inferred that the colourful palette of clothing and the accumulation of dresses stem from the durability of these garments, which is an outcome of using resilient materials. Furthermore, it reflects the women’s desire to possess garments in a broad spectrum of colours, facilitating the creation of numerous combinations using dresses and aprons.

3. CONCLUSIONS

By receiving and passing on the long-standing tradition of the kueuitl, the woman from Cuentepec serves as a vital representative of her social group. The use of the garment by the women of the community not only represents the perpetuity of the dress but also the indefinite extension of the Nahuas through time.

Moreover, the steadfast adherence to customs by the indigenous women of Cuentepec and the persistence of traditional designs passed down through generations, which maintain the authentic shapes of their attire, stand out notably. This occurs even in an era dominated by the phenomenon of fashion, characterised by its individualism and frivolity, which has permeated nearly every aspect of collective life. This phenomenon in Cuentepec is exceptional and deserving of careful consideration.

I would like to emphasise the relevance of this research given the urgent need for the field of fashion design to reformulate its role and find ways to intervene in humanity’s massive problems.

Recognising and approaching those whom the system has consistently ignored, accepting that we coexist in multiple ways and that there can be countless ways of doing things, thinking and communicating can be a first step towards a paradigm shift.

Working towards a broader understanding of human beings in order to be able to assimilate the experiences and interests of different identities and cultures is today a pending account of fashion design towards society.

NOTES

Cuentepec, like many indigenous communities, is undergoing a rapid process of acculturation. The people of the community are in continuous contact with other cultures. Communication systems and new information technologies have facilitated the relationship between indigenous people and those living in urban areas. As a consequence of this exposure to new cultural realities, the community is experiencing transformations in certain social processes. The responsibility for change falls mainly on young people, as they are typically the ones who have greater contact with global aspects. They are the ones who need to migrate in search of better educational environments or a better quality of life. It can be said that young people are the main drivers of transformation in Cuentepec.

REFERENCES

DAS, A. ALAGIRUSAMY, R. Science in clothing comfort, Cambridge: Woodhead Publishing, 2010.

GEERTZ, C. A interpretação das culturas. Rio de Janeiro: LTC, 1989.

GONZÁLEZ, C. L. Diagnóstico participativo comunitario San Sebastián Cuentepec, Morelos. México: Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos, Centro de Investigación en Ciencias Sociales y Estudios Regionales, 2020.

HERNÁNDEZ, A. Diagnóstico y perfil indígena de los Nahuas del Estado de Morelos, Perfiles Indígenas de México, Documento de trabajo, 2005.

HERREJÓN, C. ‘Tradición. Esbozo de algunos conceptos’, Relaciones, 15:59, Zamora: El Colegio de Michoacán, 1994.

INEGI (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía) Archivo histórico de localidades geoestadísticas. Histórico de movimientos de Cuentepec, Temixco, Morelos, 2020.

LANDÁZURI, G. Encuentros y desencuentros en Cuentepec, Morelos, Uam, 2002.

LARAIA, R B. Cultura: um conceito antropológico. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar, 2007.

MORAYTA, L.M. Los pueblos nahuas de Morelos: atlas etnográfico. C, México: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia: Gobierno del Estado de Morelos, 2011.

ORIHUELA G., CARMEN M. ‘El papel de las mujeres en la transición cultural de Cuentepec, Morelos’, Disparidades. Revista de Antropología, 2021.

PAZ S., MARÍA F. Viviendo en la escasez: el territorio como objeto de transacción para la sobrevivencia Economía, Sociedad y Territorio’, El Colegio Mexiquense, A.C. Toluca, México, 2009.

PINEDA J. Cuentepec apron: uses and meanings of traditional nahua clothing. Clothing Cultures. 2024. Accepted for publication.

SONG G. Improving comfort in clothing, Cambridge: Woodhead Publishing, 2011.